11. Questions 11 through 20 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Taras Grescoe, Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile. ©2012 by Taras Grescoe.

Though there are 600 million cars on the planet, and counting, there are also seven billion people, which means that for the vast majority of us getting around involves taking buses, ferryboats, commuter trains, streetcars, and subways. In other words, traveling to work, school, or the market means being a straphanger: somebody who, by choice or necessity, relies on public transport, rather than a privately owned automobile.

Half the population of New York, Toronto, and London do not own cars. Public transport is how most of the people of Asia and Africa, the world’s most populous continents, travel. Every day, subway systems carry 155 million passengers, thirtyfour times the number carried by all the world’s airplanes, and the global public transport market is now valued at $428 billion annually. A century and a half after the invention of the internal combustion engine, private car ownership is still an anomaly.

And yet public transportation, in many minds, is the opposite of glamour—a squalid last resort for those with one too many impaired driving charges, too poor to afford insurance, or too decrepit to get behind the wheel of a car. In much of North America, they are right: taking transit is a depressing experience. Anybody who has waited far too long on a street corner for the privilege of boarding a lurching, overcrowded bus, or wrestled luggage onto subways and shuttles to get to a big city airport, knows that transit on this continent tends to be underfunded, illmaintained, and illplanned. Given the opportunity, who wouldn’t drive? Hopping in a car almost always gets you to your destination more quickly.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Done right, public transport can be faster, more comfortable, and cheaper than the private automobile. In Shanghai, Germanmade magnetic levitation trains skim over elevated tracks at 266 miles an hour, whisking people to the airport at a third of the speed of sound. In provincial French towns, electricpowered streetcars run silently on rubber tires, sliding through narrow streets along a single guide rail set into cobblestones. From Spain to Sweden, WiFi equipped high-speed trains seamlessly connect with highly ramified metro networks, allowing commuters to work on laptops as they prepare for sameday meetings in once distant capital cities. In Latin America, China, and India, working people board fastloading buses that move like subway trains along dedicated busways, leaving the sedans and S U V s of the rich mired in dawntodusk traffic jams. And some cities have transformed their streets into cyclepath freeways, making giant strides in public health and safety and the sheer livability of their neighborhoods—in the process turning the workaday bicycle into a viable form of mass transit.

If you credit the demographers, this transit trend has legs. The “Millennials,” who reached adulthood around the turn of the century and now outnumber baby boomers, tend to favor cities over suburbs, and are far more willing than their parents to ride buses and subways. Part of the reason is their ease with iPads, MP3 players, Kindles, and smartphones: you can get some serious texting done when you’re not driving, and earbuds offer effective insulation from all but the most extreme commuting annoyances. Even though there are more teenagers in the country than ever, only ten million have a driver’s license (versus twelve million a generation ago). Baby boomers may have been raised in Leave It to Beaver suburbs, but as they retire, a significant contingent is favoring older cities and compact towns where they have the option of walking and riding bikes. Seniors, too, are more likely to use transit, and by 2025, there will be 64 million Americans over the age of sixtyfive. Already, dwellings in older neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Denver, especially those near light-rail or subway stations, are commanding enormous price premiums over suburban homes. The experience of European and Asian cities shows that if you make buses, subways, and trains convenient, comfortable, fast, and safe, a surprisingly large percentage of citizens will opt to ride rather than drive.

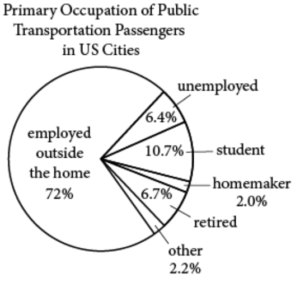

Figure 1.

Begin skippable figure description.

The figure presents a circle graph titled “Primary Occupation of Public Transportation Passengers in U S Cities.” The graph is divided into 6 different sectors. The respective percents are labeled, clockwise, as: unemployed, 6.4 percent; student, 10.7 percent; homemaker, 2.0 percent; retired, 6.7 percent; other, 2.2 percent; and employed outside the home, 72 percent. Each sector has its own percent label.

End skippable figure description.

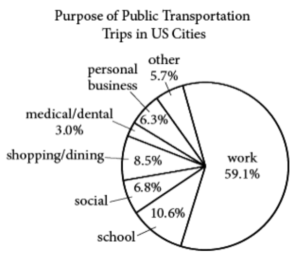

Figure 2.

Begin skippable figure description.

The figure presents a circle graph titled “Purpose of Public Transportation Trips in U S Cities.” The graph is divided into 7 different sectors. The respective percents are labeled, clockwise, as: work, 59.1 percent; school, 10.6 percent; social, 6.8 percent; shopping/dining, 8.5 percent; medical/dental, 3.0 percent; personal business, 6.3 percent; and other, 5.7 percent.

End skippable figure description.

Source: Figure 1 and figure 2 are adapted from the American Public Transportation Association, “A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics Reported in OnBoard Surveys.” ©2007 by American Public Transportation Association

Question 11.

What function does the third paragraph serve in the passage as a whole?